Ortiz Miranda described examining a late-18th-century book that had a curious use of green in its religious illustrations, such as on chalices and halos. The verdant color is frequently a sign of arsenic. She instead found these sections were intended to appear gold, but the metal alloy of copper and zinc had degraded. Yet arsenic was present and, strangely, not only in the green areas. “I did more analysis on the covers, paste-downs, spine, everything that I didn’t run by the first time, and indeed it was an arsenic base from an inorganic pesticide,” Ortiz Miranda said.

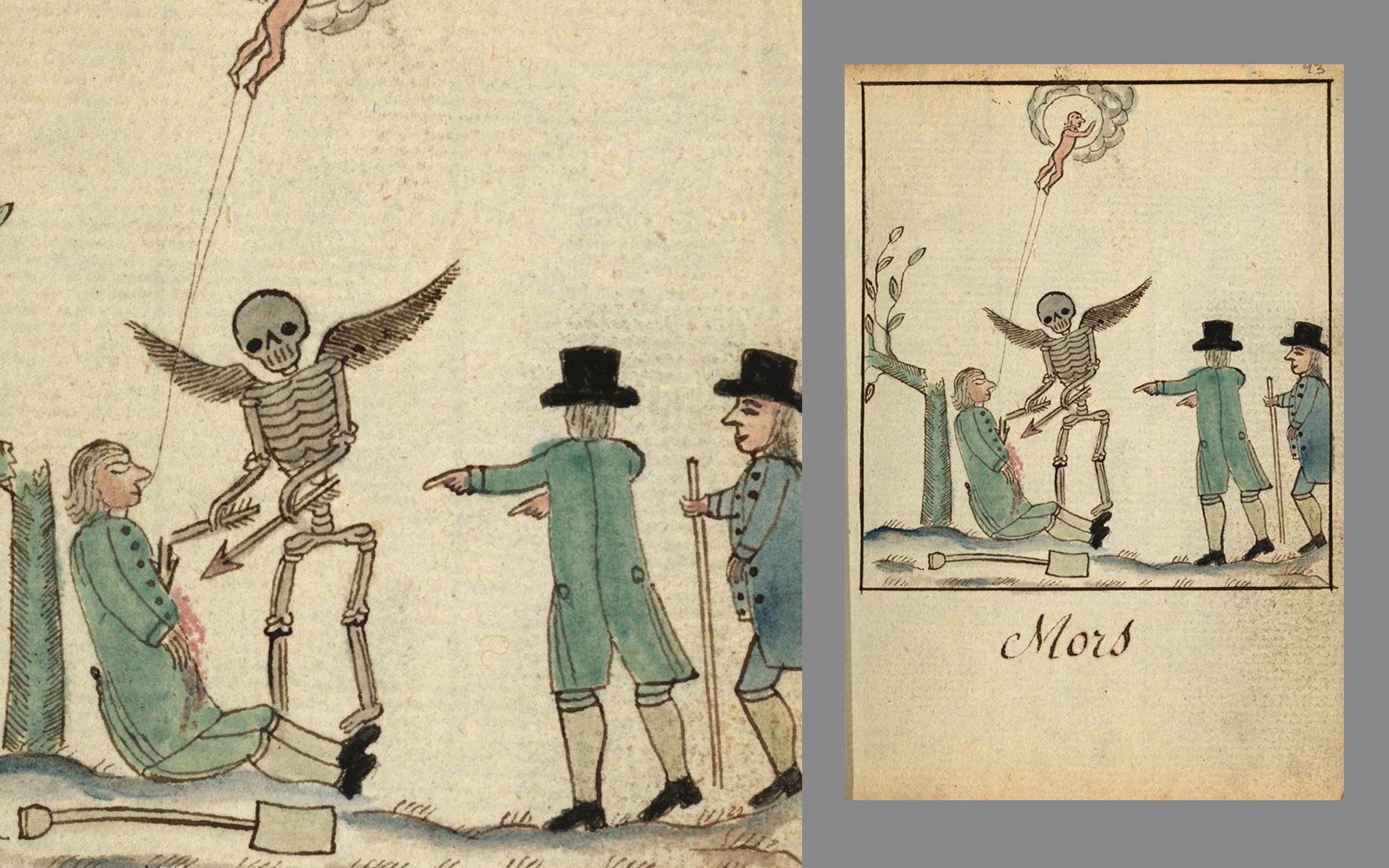

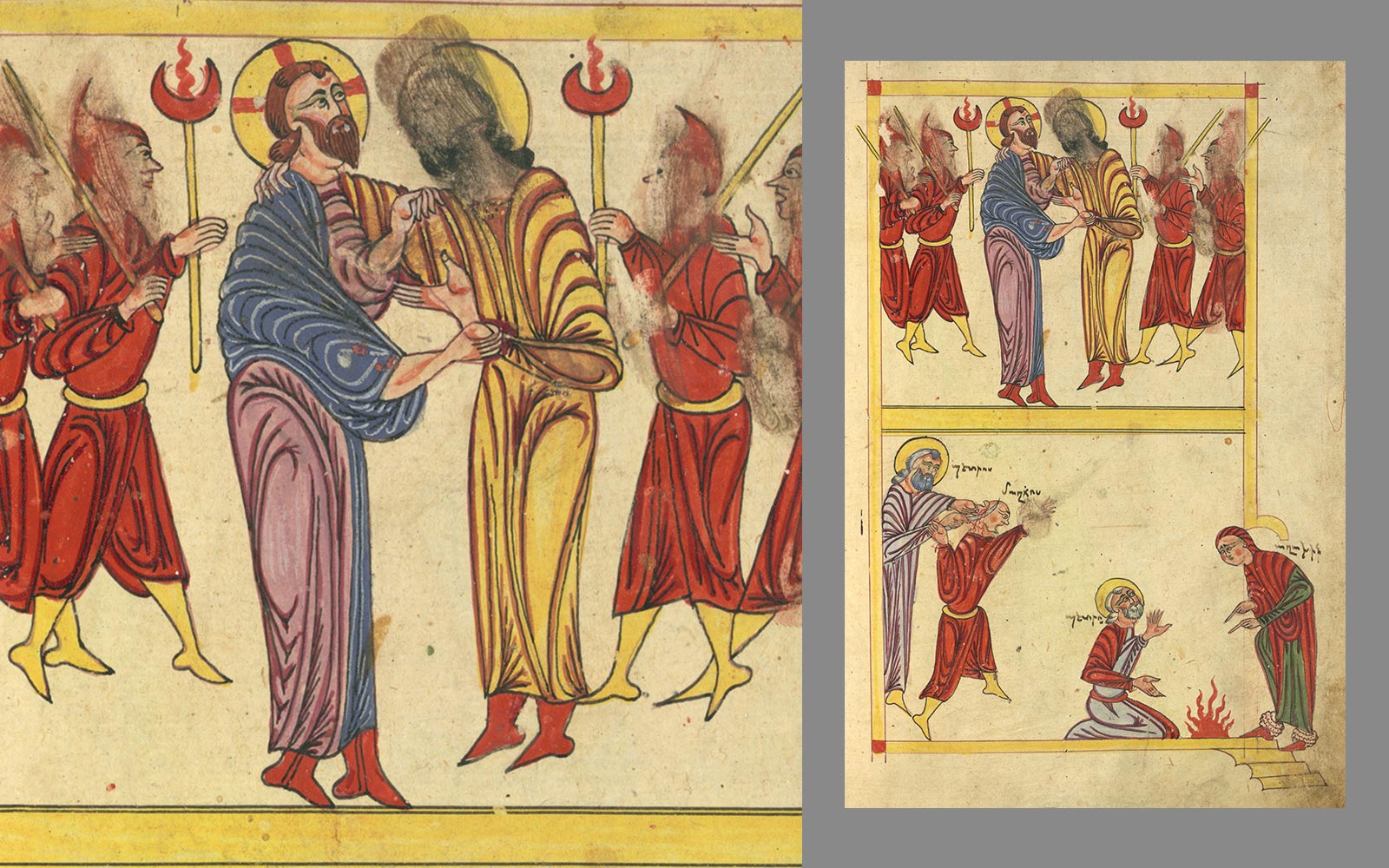

Although some manuscripts treated with pesticides to protect them from insects like bookworms were stamped, many were not, making this danger much harder to detect compared to telltale colors in pigments. If Books Could Kill includes examples from across centuries of global culture to show the pervasiveness of such perils, from a 1455 Armenian gospel book accented with bright red vermillion containing mercury from powdered mineral cinnabar to an 1824 treatise on elephants from Thailand with brilliant yellows made from orpiment, an arsenic sulfide mineral.

“We wanted to tell stories not just of these materials that you can find in every museum, because they were common, but also of these books as something personal and intimate,” Ortiz Miranda said. “You don’t handle a book in the same way that you handle a painting or a ceramic.”

The tactile relationship between a reader and these manuscripts could be even closer than simply touching the pages, such as with books with images of the wounds of Christ accompanied by a prayer. “You’re meant to kiss the picture,” Herbert said. “There is a manuscript where you can see clearly that the wounds had been kissed over and over again, to the point where the image is starting to get worn away. And knowing that it was painted with a paint that had mercury in it made me think about that person engaging with the book. What would that have done to them?”

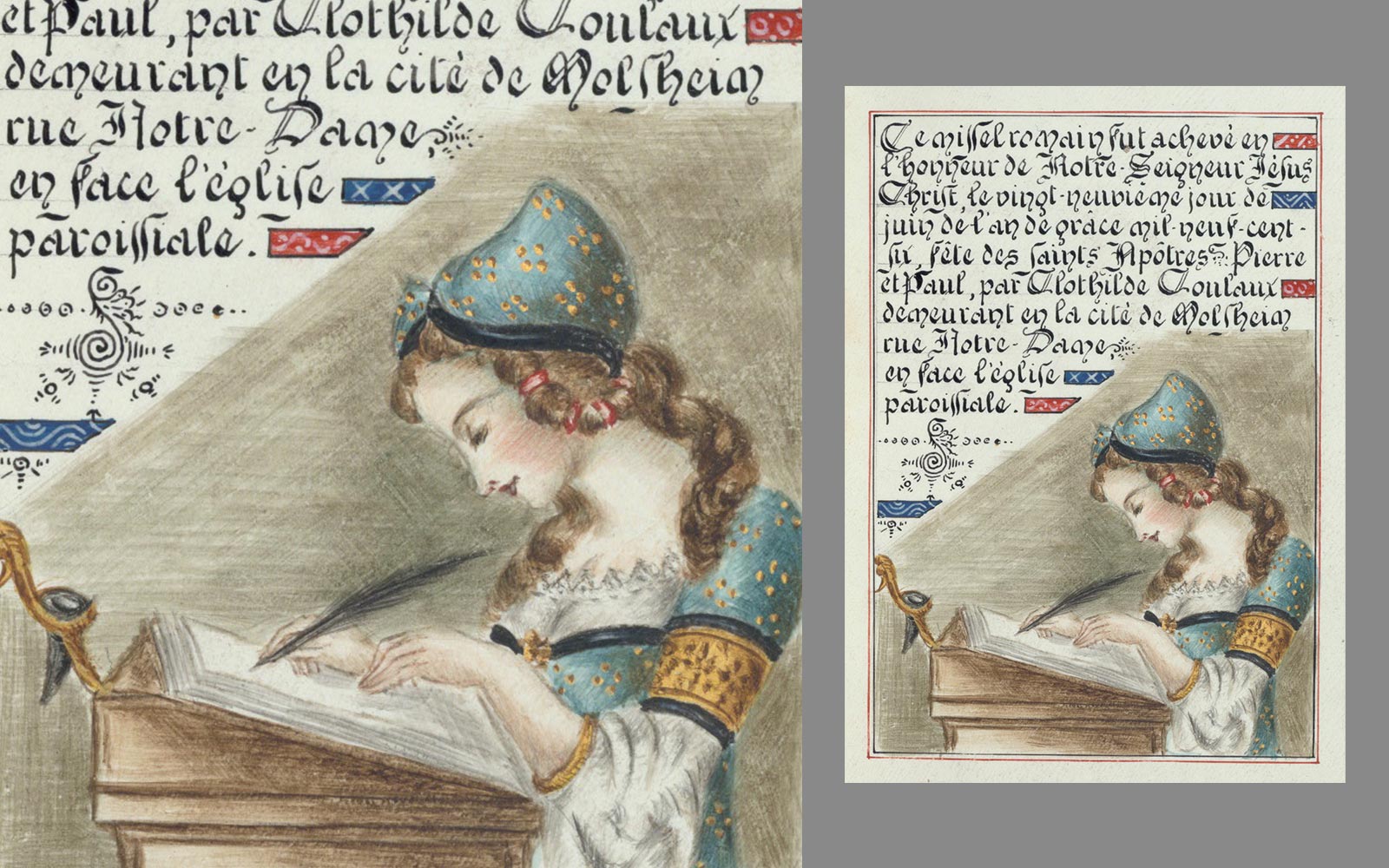

The book dealer that had the Clothilde Missal before the Walters hadn’t been aware of lead on its pages, and the curators of If Books Could Kill hope that this exhibition doesn’t just reveal the dangers of the past but heightens awareness of the potentially harmful materials in historic manuscripts, whether they’re hinted at by startlingly vibrant colors, or are nearly invisible within the pages.