The new letterlocking book is both a foundational text and a hands-on guide, featuring over 300 diagrams and a dictionary of sixty technical terms. The authors believe deeply in “learning by doing” and invite readers to create their own models. “The main reason you should give this a go is because it’s fun,” said Smith. “There’s something utterly absorbing and fascinating about figuring out these techniques—then delighting a friend with an unexpected delivery in the mail.”

Of course, there’s more at stake. Dambrogio said that one of their goals with the book was to “illustrate how, throughout history, people have actively sought to connect through letters while ingeniously protecting their messages from prying eyes during transit.”

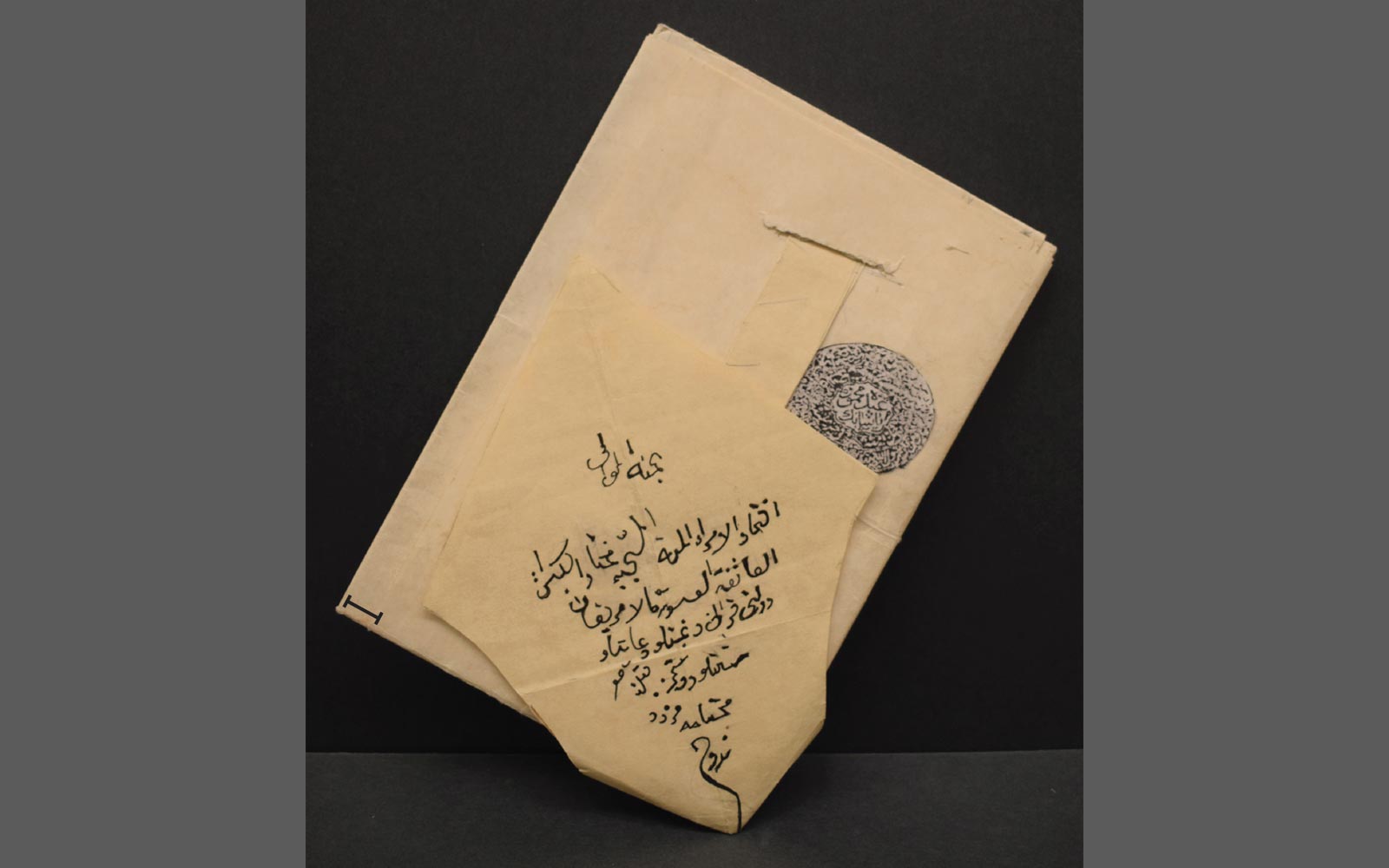

Studying these techniques can also offer new scholarly opportunities. As Smith put it, “In an increasingly digital world, we have an opportunity through letterlocking to think about the ways that material artifacts have carried meaning.” After all, letterlocking wasn’t a single tradition but a constellation of techniques adapted by kings, spies, lovers, and bureaucrats. It was used by Elizabeth I’s courtiers, by Japanese samurai, and by poets like John Donne, whose sealed packets, the pair realized early on, were not only secure but characteristically playful. Indeed, the choice of a letterlocking technique could reflect not just security concerns, but also aesthetics, etiquette, or tradition.

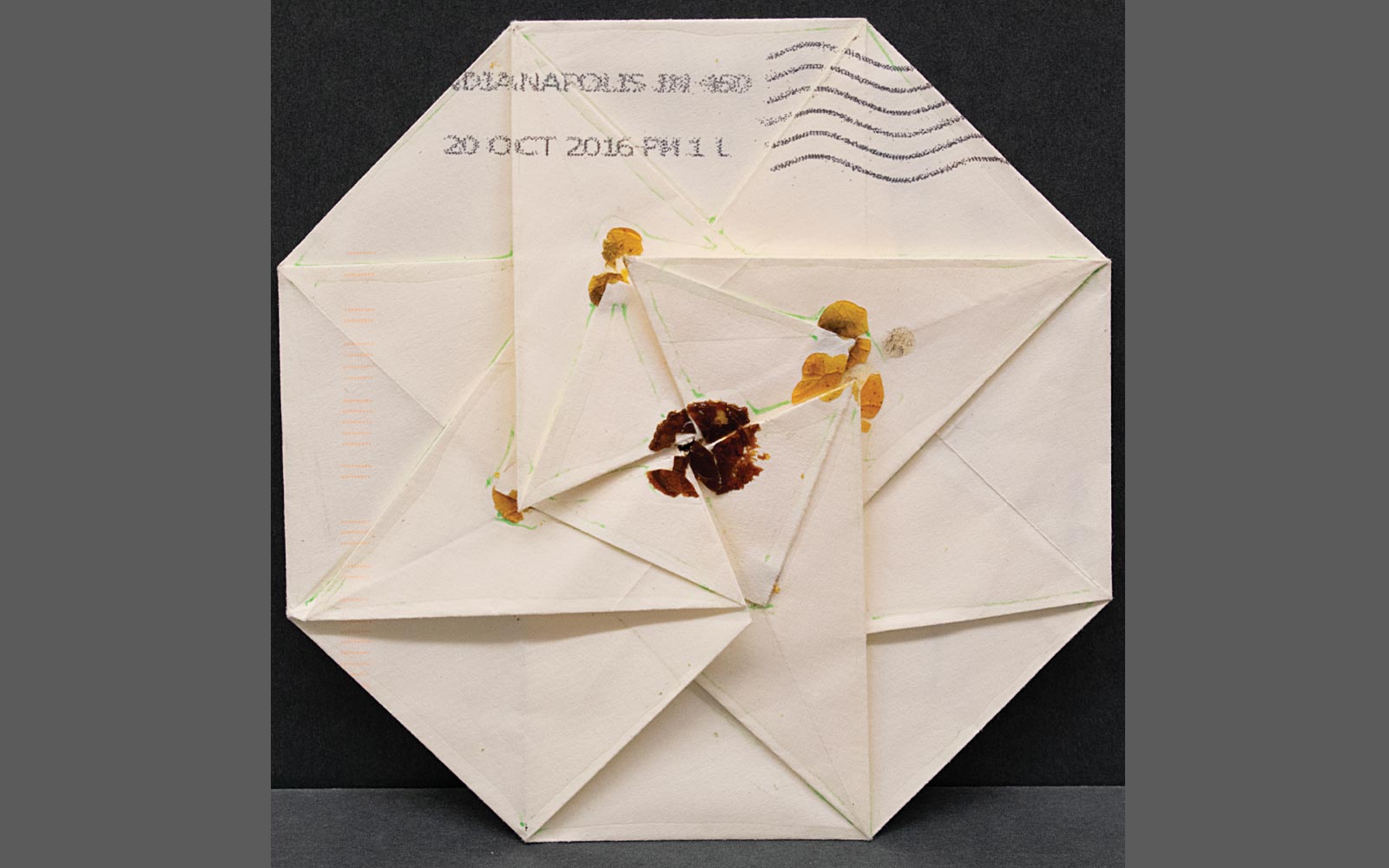

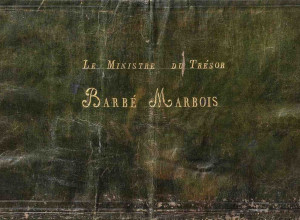

One striking example comes from a 1798 letter sent between two Freemasons and addressed to Lieutenant George August Dossit D’Alban. It was found in the Prize Papers, a collection held in the UK’s national archives that includes thousands of letters and objects intercepted by British privateers and naval vessels. The paper of the letter is folded into a long strip, then folded again and twisted into something almost like a bow on a present. “We call this the nonagon because it has nine sides, but it also has another really interesting feature,” Smith said. “At the center of this packet is a triangle, a shape important to Masons because of their special interest in the mathematical theories of Pythagoras.”

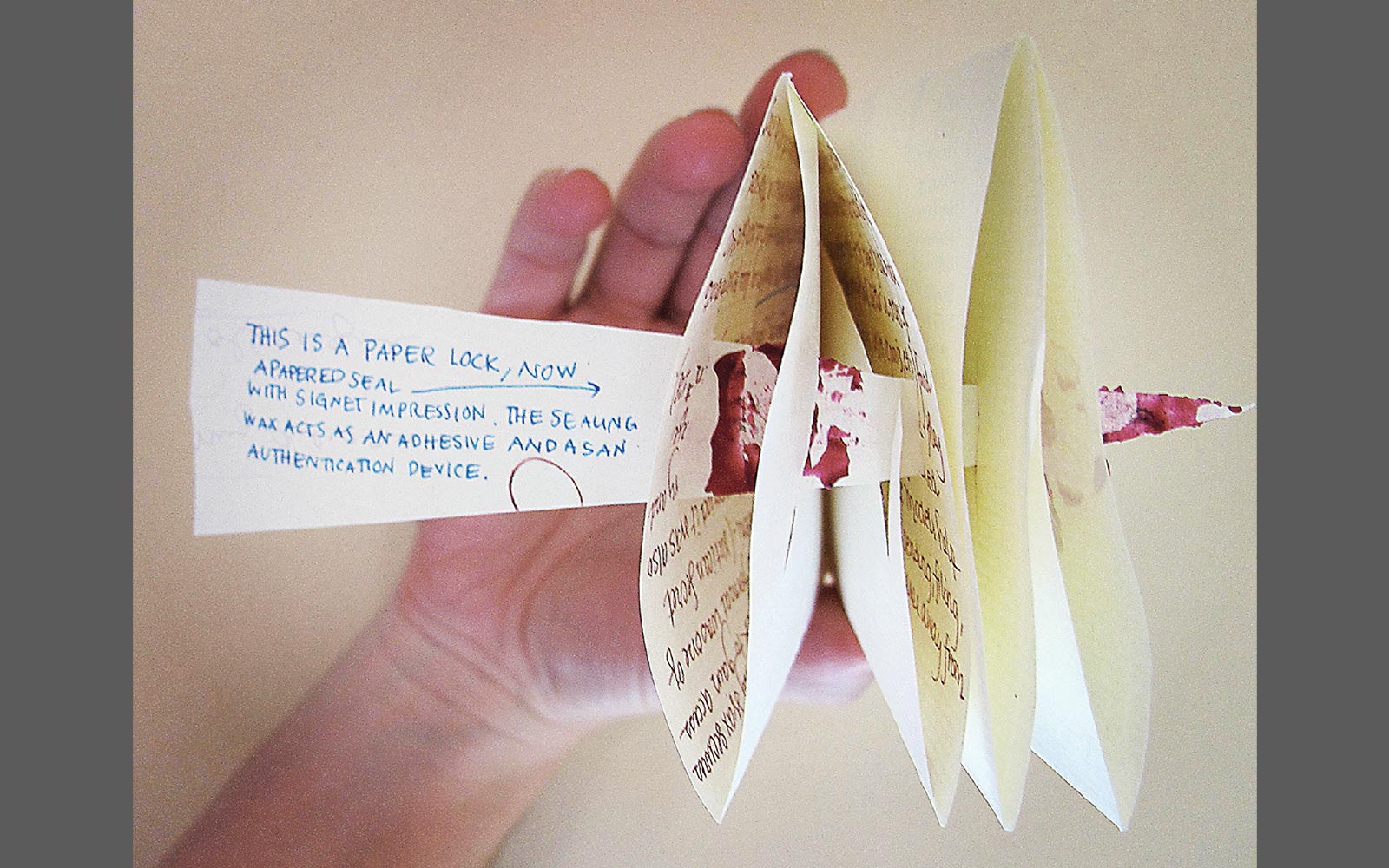

The book, and the letterlocking field as a whole, also aims to be a boon for research and conservation. The authors have identified sixty-four letterlocking categories, based on the folds, tucks, and other manipulations that transform the letter into its own “letterpacket.”

“These manipulations and features … often mimic damage,” Dambrogio explained. “It is crucial in the study of letterlocking to distinguish between actual damage, like worn holes, and manipulations. Confusing the two can lead to the unintentional concealment of vital information during repairs, hindering letterlocking scholars in accurately identifying and categorizing the letters.”

In an era when many people have moved their private conversations to encrypted apps such as Signal, the questions raised by letterlocking feel newly resonant. “We’re conscious that we’re releasing a book about the history of letters at a time when many people no longer send letters,” Smith said. “But the privacy of our communication—or, as we might say today, the security of our private data—remains a vitally important topic.”