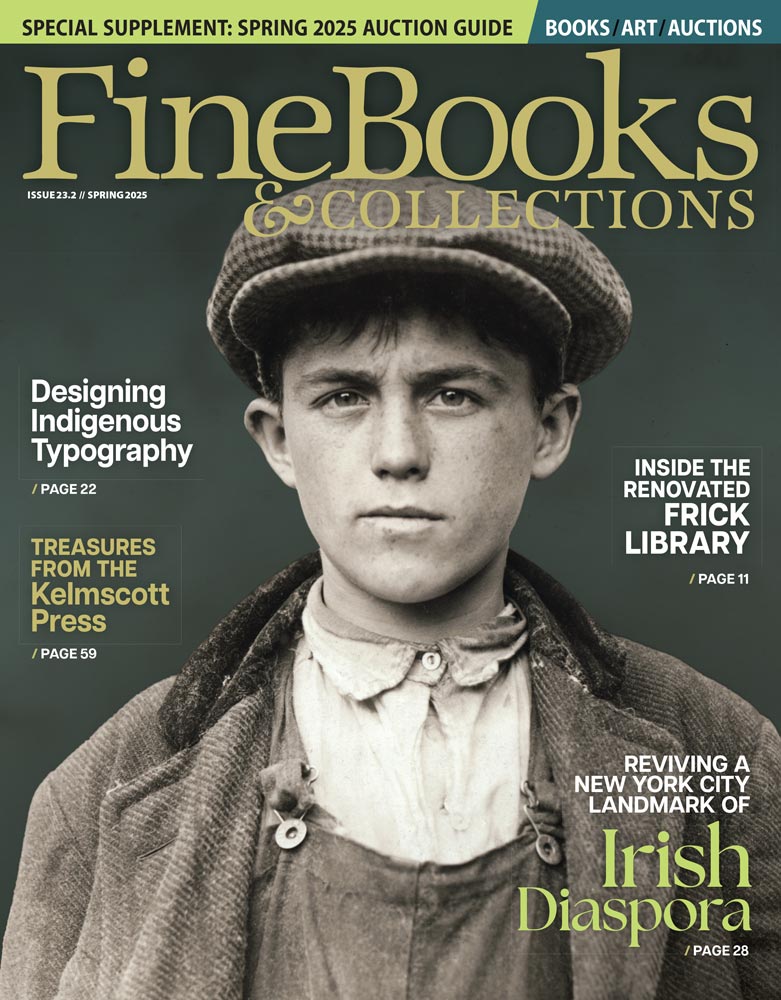

Archiving the Black Web Director Zakiya Collier on Audre Lorde Manuscripts and Memory Work

Zakiya Collier

Our Bright Young Librarians series continues today with Zakiya Collier, an archivist and memory worker in New York City:

Please introduce us to your role as an archivist and memory worker:

As an archivist and memory worker, I center the documentation, preservation, and celebration of Black experiences and culture. Primarily, this includes working with Black individuals and organizations to support them in managing their archival collections or strategizing to organize their archival and cultural memory projects. My memory work can take several different forms. I’m currently the Program Director for Archiving the Black Web, where I oversee the newly developed flagship program, Web Archiving (WARC) School, and a community of fellows, instructors, and TAs. I also serve as an archival consultant for artists and artist foundations like the visual artist, Marilyn Nance, and the Valerie J. Maynard Foundation. I adjunct in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at Queens College, CUNY, teaching courses like Community Archives and Libraries and Information Activism.

And this year, I’m thrilled to be a 2025 Create Change Artist-in-Residence at The Laundromat Project. My project, Collective Remembrance, uses an intergenerational and creative, collective archival approach that directly fosters and resources relationships between Black elders and local Black archivists and memory Workers, to share and document Black Brooklyn history and strengthen the local Black memory work ecosystem. In all my roles, I cultivate communities of practice of collective stewardship to remind us all that the preservation of our histories is our collective responsibility.

Please introduce us to the Black Memory Workers:

Black memory workers is a group of 300+ Black-diasporic archivists, curators, educators, stewards, genealogists, family historians, community organizers, oral historians, technologists, artists, creators, storytellers, and students that are committed to practicing care and intention as we prioritize the documentation, long-term preservation, and celebration of Black life and experiences. It began in a virtual gathering and support space of 30 memory workers in June 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic and protests against police violence.

We collectively authored and offered a call to action to ethically and comprehensively archive the Black experience with Black memory workers at the forefront and to call attention to the oppressive systems both inside and outside of archives and libraries that disproportionately subject Black people to generational violences and extractive institutional efforts to document our experiences. Since 2020 we’ve been meeting monthly and participating in on and offline discussions on how to sustain and better support our work with(in) Black communities and in traditional archival institutions while prioritizing care over capital.

How did you get started in archives and memory work?

At the age of six, I began stewarding the collection of photographs, certificates, artworks, and mementos documenting my life and the lives of my loved ones. Holding history in my hands, I was transformed by the power of remembering myself. I spent my childhood years preserving, cataloging, indexing, labeling, curating, installing, and deinstalling mini-exhibitions on my bedroom walls. I rented storage units from ages 18-21 to process my materials. I spent many days alone in those units thinking about all the archival materials other folks held, and also wishing I could convince my college-aged friends to join me in these journeys through history. Eventually, I learned that this is something I could do professionally, creatively, and collaboratively–and with and for everyday Black communities living rich lives that may never end up in the media or archival institutions.

Although I had done archival research and conducted oral histories in my undergraduate thesis research, I didn’t have a conceptual understanding of archival work as a profession or community of practice until later in graduate school. Through my coursework in Black studies, Black feminist theory, and visual cultural studies, I came to understand the archive as a physical space where historical materials are held, but also as a space where Black life and experiences have been erased and or excluded. After realizing that the practices I had been doing most of my life were archival, I went full steam ahead into becoming an archivist/librarian through a library science program.

Fortunately for me, my MA program offered a dual degree option, and I’ve been on this path ever since. From the beginning, I have been interested in and committed to an exploration and celebration of Black archival practices, or archival practices that account for the material conditions of Black life and the ways it is lived, as opposed to fitting Black life into traditional archival practices that were never intended to hold us.

Where did you earn your degrees?

BA in Anthropology from the University of South Carolina

MA in Media, Culture and Communication from New York University

MS in Library and Information Science (MLIS) from Long Island University

Advanced Certificate in Archives and Records Management from Long Island University

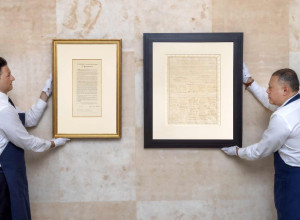

Favorite rare book / ephemera / archival piece that you've handled?

My favorite archival piece that I’ve handled is probably Audre Lorde’s manuscripts at the Spelman College Archives. It was such an out-of-body experience to hold the original versions of texts that have touched and transformed my life in more ways than one.

What do you personally collect?

Whew… so many things from ephemera to memorabilia. I collect books from Black women writers, materials from Black political movements /groups, zines, buttons, pins, stickers, playbills, flyers, cards, letters, websites, obituaries, and so much more that I’m sure I’m forgetting. I’m pretty intentional about coming home with some piece of ephemera from events I attend, spaces I contribute to, and communities I’m a part of since they play such an important role in my life as they inform my thinking, my living, my being. That especially includes gathering and preserving materials documenting my friends’ events, accomplishments, creations, websites, etc, even if I’m not physically present for the occasion.

I’m always the one asking, “Did you get me a copy of the program?” “Are there physical tickets?” “Can you send me the link?” “Can you let me know when you’re about to delete your Instagram or website?” Like many of the memory workers before me, I think documenting my community and the world from my vantage point - its injustices, its beauty, its changes, is just as important as documenting my own experiences - my journals, my publications, my photos/videos, my documents, my purchases, my press features, my medical records, my relationships…

Lastly, I also collect thousands of digital photos and screenshots like the rest of the world. This worries me because, like, what do we do with tens of thousands of digital photos each? We can’t print them all, look at them all, understand them all? But it feels comforting to have, I guess!

What do you like to do outside of work?

Outside of work, you can find me at pilates, traveling, reading, spending time with friends, and enjoying the amazing programs organized by my amazing community of friends and colleagues.

What excites you about archives and memory work?

I’m excited when I reflect on how archives and memory work affirm people’s existences, provide opportunity for people and communities to connect and build solidarity and sustainability through documented shared experiences, and offer a unique entry point into our interiorities, which are so often hidden or silenced.

Thoughts on the future of memory work?

I’m feeling very encouraged about the future of memory work, as more than ever before, there are Black and Indigenous folks independently involved in memory work to document themselves and their communities. We have always done memory work, but now more people are talking about their work, making their processes and collections available through social media, digital archives, and community gatherings. Even in the face of attempts to erase our histories, I’m hopeful that with more people committed to cultural preservation and collaborating in their efforts, our collective histories and memories will survive, and so will we.